Flight Control System Design

Flight Control System Design

Effective Date: 15 October 98

C. A. Mason, Engineer Specialist, and

The term "fin stall," as it applies to the Hercules aircraft, is often misunderstood. There is a small group of C-130 aircrew members who are convinced that almost any sideslip excursion brings on fin stall. Others believe that any fairly rapid yawing motion beyond that expected of the typical student pilot can cause the laws of physics and aerodynamics to be repealed and control of flight to be lost - all under the banner of fin stall.

The truth of the matter is that the Hercules aircraft is not susceptible to fin stall under these circumstances, and the term fin stall itself is inaccurate when applied to the Hercules in such situations.

So what is really going on? The large power effects created by the propeller slipstream that make the Hercules such a great short-field tactical transport also mandate a large vertical stabilizer (fin) for directional stability, with a large rudder for low-speed control of asymmetric power from the engines. These features also had to be considered when it came to engineering the flight control system.

At the time of the C-130's design in the early 1950s, a propeller-powered transport aircraft did not justify the cost and complexity of the fully powered, irreversible flight controls that are used on many aircraft today. A more conventional reversible system was selected instead. Each control surface was sized to provide the control power required, and a hydraulic booster was added to assist the pilot in situations where the forces needed to move the controls were too heavy for manual power alone.

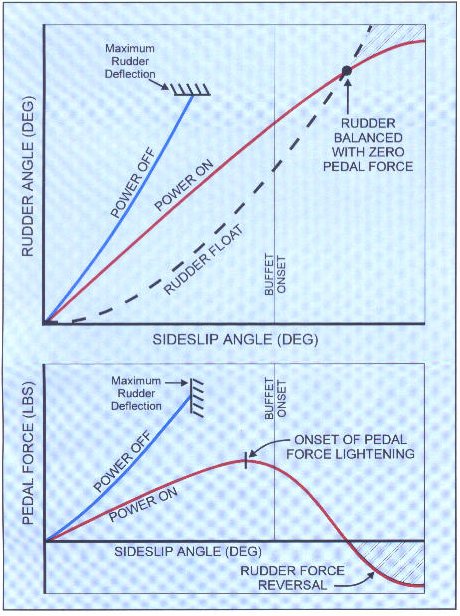

One characteristic of this type of system is that the pilot enjoys excellent feedback from the flight controls. He is directly connected to the main control surfaces and can feel each surface's position and the force necessary to hold it or move it. Another characteristic is that in the absence of inputs from the pilot, the rudder will "float" to an angle where the aerodynamic loads on the rudder are zero.

During straight flight, these same aerodynamic loads cause the rudder to float at the neutral position, and the pilot must apply pedal force to push the rudder out to a given deflection. All other things being equal (equal power on all engines, etc.), the airplane nose will move in the same direction as the rudder when the rudder pedal is depressed. A small sideslip angle will then develop, which pulls the opposite wing up and results in a turn.

If, instead, the pilot lowers the wing to bank in the direction opposite the turn, a steady-heading sideslip will result. The airflow now hits the vertical fin from the side opposite the rudder. This off-centerline flow acts to reduce the rudder force that the pilot had to overcome initially, and the difference in rudder pedal force can actually be felt by the pilot. Engineers call these forces "hinge moments" because they really are moments trying to rotate the rudder surface about its hinge line. Pilots prefer just "forces" because that is what they apply to the pedal.

If the rudder angle required to maintain a given sideslip angle is greater than the float angle for that amount of sideslip, then pedal forces must be applied to keep the rudder from returning toward neutral. As sideslip angles increase toward the higher angles, there is a tendency for the rudder to float out more rapidly and less pedal force is required to hold the rudder deflection.

A point is finally reached where the rudder angle required to hold the sideslip angle and the rudder float position are identical. At this point the rudder stays where it is with no pilot force on the pedals. In effect, the rudder is balanced with zero pedal force (Figure 1). The term "rudder lock" is sometimes applied to this point, but this is misleading because the rudder is not actually locked. It does require force on the opposite pedal to return to a normal flight attitude, but the rudder will readily respond to that restoring pedal force.

Figure 1. A graphical representation of the relationship between rudder angle and pedal force during sideslip manuevers in the Hercules aircraft.

Beyond this point, the pilot must apply opposite pedal force to restrain the rudder from floating further out. This is rudder force reversal, also called rudder overbalance. It is not fin stall, because the airplane remains directionally stable and will return to straight flight if the rudder is returned to neutral and the wings are leveled.

Getting into rudder force reversal requires abnormally high sideslip angles, which are prohibited by the flight manual. Rudder force reversal is preceded by heavy, unmistakable buffet on the vertical tail (but not fin stall) that usually begins between 16 and 24 degrees of sideslip. A noticeable reduction in rudder pedal force starts at about 17 degrees of sideslip.

Further increases in sideslip produce large yawing transients and a reversal of pedal forces. If the pilot lets the rudder float and does not reduce the sideslip, the aircraft will yaw out to a sideslip angle of 40 to 45 degrees. The nose-up pitching tendency that occurs simultaneously can cause one wing to stall. The airplane is now in very serious trouble! Both lateral and directional stability have been lost and recovery is problematic at best.

Susceptibility to encountering rudder force reversal is greatest at low speed and high power (usually 75% power or greater) with flaps extended. It has never been reported in a power-off condition. Power effects on the wing and fuselage of the C-130 reduce the directional stability level sufficiently so that rudder force reversal occurs before fin stall.

Recovery from a rudder force reversal condition requires returning the rudder to neutral and can be assisted by rolling wings-level, pushing the nose down to decrease angle of attack, and reducing power; but only if altitude permits.

.

So does fin stall really exist? Theoretically, yes. Any lifting surface will stall if given enough angle of attack. The vertical fin is a lifting surface, and sideslip is just angle of attack viewed from overhead. What happens in true fin stall is complete separation of the airflow over the fin and rudder. Just like a wing stall, complete airflow separation over the fin removes its horizontal "lift," or side force. Directional stability is then lost because the restoring tail moment, which is totally dependent on that side force, disappears.

However, getting fin stall to occur on a Hercules requires sideslips far beyond the flight manual limits and much hard work on the part of the pilot, all in the wrong direction, of course. Extensive wind-tunnel testing and much flight testing have shown that the Herc' s vertical tail does not stall, even out to sideslips as high as 30 degrees.

But don't go out and try to verify this! Fin stall is outside the flight manual limits. You will get into rudder force reversal well before getting that high a sideslip angle, and you risk loss of the airplane if improper flight control inputs are made. Also, you have no real way of measuring sidelip angle with the instruments provided on your instrument panel, and the indicated airspeed becomes unreliable at large sideslip angles. Any line pilot who intentionally investigates this condition should seriously consider another line of employment.

It must be kept in mind that the turn and slip indicator, the "slip ball" on the instrument panel, is not a sideslip gauge. The slip ball, or slip-skid ball if you prefer, reacts only to one thing: lateral acceleration, whether that acceleration comes from aerodynamic forces, inertia forces, gravitational forces (due to bank angle), or any combination of these. In particular, the slip ball should not be considered a primary reference during engine-out flight.

When the Hercules is being flown correctly under engine-inoperative conditions, the ball may be slightly displaced from the center toward the good engines; but the amount of displacement varies with airspeed, bank angle, altitude, air temperature, and aircraft gross weight. DO NOT use the ball as an attitude reference during asymmetric thrust situations.

Now consider the following scenario: You are exiting the drop zone on a formation drop and hit the wake of the Hercules that has crossed in front of you. The airplane rolls and yaws pretty violently and you feel the rudder try to go hard over all by itself. You push the rudder back to center with strong pressure on the opposite pedal and recover to wings level.

Was it fin stall? No, because you did not lose directional control. Was it rudder force reversal? Perhaps, but only for the brief time you were passing through the wake. As soon as you cleared the wake, the rudder would have returned to neutral on its own. Yes, it was scary, but should you have also pushed the nose over and reduced power? Not at that low altitude. The situation would have returned to normal once you exited the wake, given enough time, altitude, and speed. But it is better to know what was going on and react accordingly.

Here is another scenario: A training flight is being conducted to give the student pilot experience flying the C-130 with an engine inoperative. Under the guidance of an instructor pilot, the student is performing a series of approach and go-around maneuvers with the No. 1 engine simulated inoperative. He is being careful to keep his speed above the charted air minimum control speed.

Following the go-around, the flight crew begins an air traffic control-directed left turn at 1,700 feet above actual ground level. The student pilot relaxes the right rudder in a misguided attempt to keep the turn coordinated and the ball centered. The aircraft yaws rapidly to the left, pitches over, and begins a steep decent. In just 25 seconds the aircraft hits the ground, before control can be regained and recovery from the dive completed.

Was this loss of control caused by fin stall or rudder force reversal? Neither one! We have already seen that the fin does not stall at small yaw angles. In this engine- out scenario, the asymmetric power condition produces a left yaw which is being controlled by right rudder. Rudder force reversal does not occur when the rudder control input is opposing the yaw.

Improper use of the rudder, combined with improper bank angle, produced this loss of control. Maintaining air minimum control speed (Vmca) ensures only that the airplane can be controlled in steady flight at the prescribed conditions of maximum rudder (or pedal force), favorable bank angle, etc. It does not ensure additional yaw control for maneuvering, recovering from further upsets, or relaxing favorable bank angle or rudder deflection.

With No. 1 engine inoperative, turns should be made to the right to avoid the large increase in Vmca caused by the adverse bank angle. Remember that you, not the air traffic controller, are flying the airplane. The controller most likely does not know or comprehend the importance of maintaining a favorable bank angle during engine-out operation at low speeds. Make sure that you communicate your problem (simulated or real) to air traffic control and tell them what you plan to do.

To prevent departures from controlled flight, especially during engine-out situations, the following guidelines are suggested:

While the probability of encountering rudder force reversal in flight is very remote, it is important that you know about this flight characteristic, know how to avoid it, and know how to recover from it. Even more important is that you fully understand the aircraft's handling qualities with an engine inoperative.

The low-speed limits specified by the air minimum control speeds and stall speeds are intended to prevent operation at airspeeds where any sudden loss of engine power or reduction in control capability would cause loss of control of the aircraft. The effects of bank angle on minimum control speed and on stall speed are significant and must be respected.

Charles Mason and Scott Barland may be reached at 404-494-4881 (voice), or 404-494-3055 (fax).

Charles Mason and Scott Barland may be reached at 404-494-4881 (voice), or 404-494-3055 (fax).